We need your support to keep the secularist going

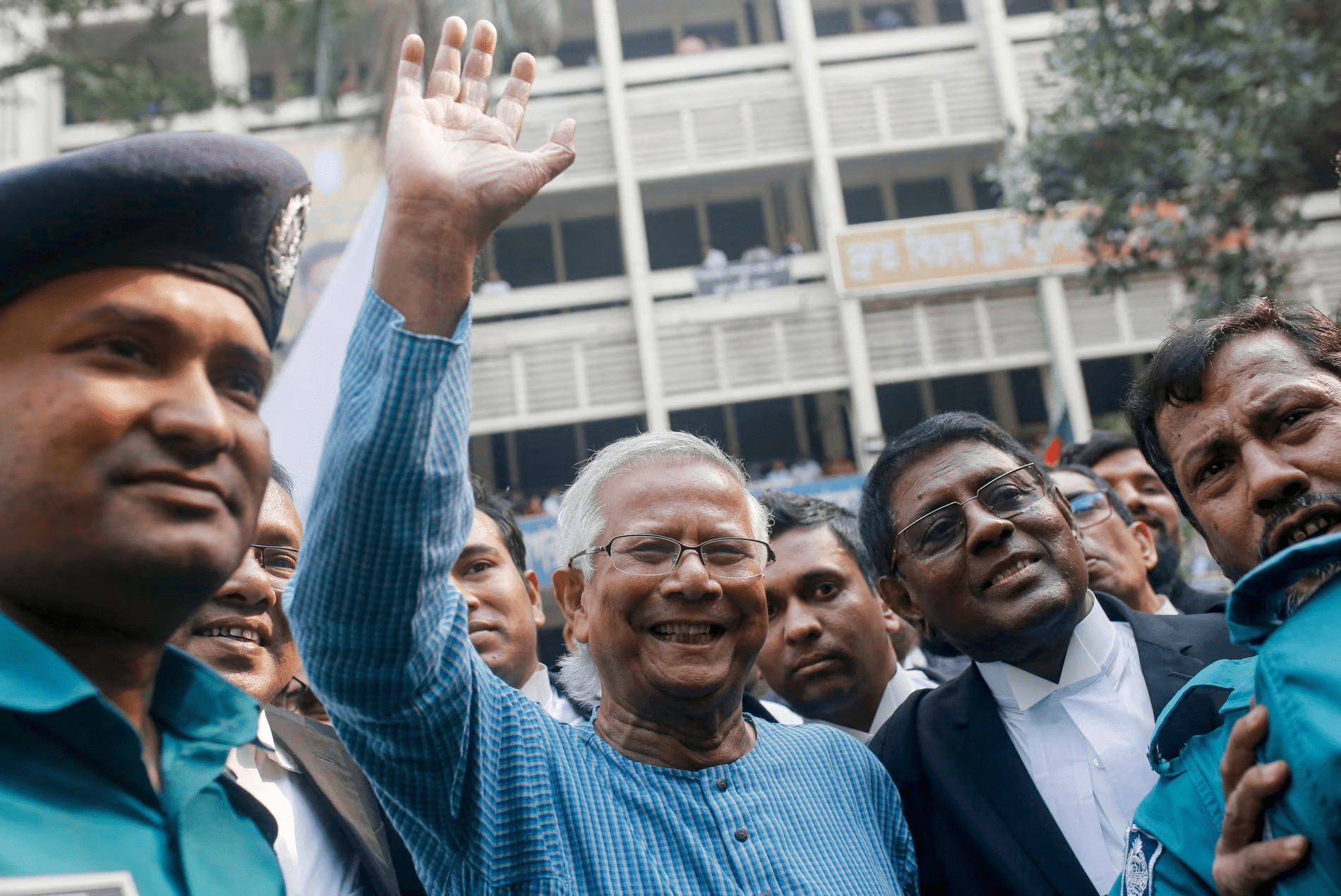

Muhammad Yunus waves to supporters outside a court in Dhaka where he was granted bail on 3 March. Photograph: Rehman Asad/AFP/Getty Images

The Nobel peace laureate and microfinance pioneer Muhammad Yunus has said that years of fighting what he calls “dirty” politically motivated attacks on his work to alleviate poverty in Bangladesh have made life “totally miserable”.

Yunus told the Guardian he had come under 20 years of pressure from the Bangladeshi government for his work, which is credited with improving the lives of millions of poor people, particularly women.

In January, he was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, along with three other people, for violating labour laws at Grameen Telecom, the not-for-profit company he founded in 1983. He is now on bail pending an appeal but has been charged with more than 100 other crimes, all of which he denies.

“This thing continues and makes my life miserable,” said Yunus. “I can’t concentrate on anything because I’m busy digging up documents to prove that I didn’t do this, documents to prove that I never did that.”

Yunus is credited with pioneering microfinance, a financial service for people locked out of formal banking systems. It allows them to take out small loans to invest in building their own businesses. Piloted in 1976 among a group of women in a Bangladeshi village who were given small loans without needing collateral, by the mid-2000s it was seen as a key tool for ending poverty. Yunus and the Grameen Bank won the Nobel peace prize for the work in 2006.

The system’s success in lifting people out of poverty has since been questioned and microfinance has been the subject of several scandals over lenders charging exploitative interest rates.

In 2011, Yunus was forced to resign from Grameen after a campaign led by Bangladeshi politicians. Yunus, who was 70 at the time, was deemed too old to run the bank. He maintains the mandatory retirement age of 60 should not have applied to him as the bank was not a government institution.

The Bangladeshi government has defended the action against Yunus, and denies that it represents a misuse of the legal system, accusing the economist of having a “victim mentality” for claiming he was being personally harassed.

Last year, more than 100 Nobel laureates signed an open letter calling for the labour law charges to be suspended. Amnesty International said the case was “emblematic of the beleaguered state of human rights in Bangladesh, where the authorities have eroded freedoms and bulldozed critics into submission”.

Alongside the January conviction, Yunus has been charged with corruption, tax evasion and money laundering.

“These are all false, ask any Bangladeshi. Anybody will know this is all false, fabricated,” Yunus said.

Bangladesh’s prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, has accused the microfinance sector of “sucking blood” from the poor, but it was a speech she made in 2022 during the opening of the country’s long-awaited Padma Bridge that particularly concerned Yunus.

Hasina accused him of blocking progress on the bridge, which had a $1.2bn (£940m) World Bank loan cancelled in 2012 over allegations of corruption by Bangladeshi officials. She called for him to be plunged into the river to “teach him a lesson”. “It’s a very dangerous thing we are inviting the people of the country to dunk someone [in the river],” Yunus said. Hasina “pours out her extreme hatred on me”, he added.

Yunus won’t be drawn on the reasons for Hasina’s enmity but it has been linked by others to his aborted attempt to launch a political party in 2007.

Despite the threat of imprisonment, the 83-year-old has remained in Bangladesh and is still working to eliminate poverty and unemployment.

He said other countries had offered to host him but he did not want to leave behind his work or his employees. “This will be all forgotten, removed, destroyed. I don’t want to see that.

“Leave me alone, let me do the thing I want, that I enjoy doing and that people benefit from. It is not for my own interest,” he said. “I enjoy finding out solutions for the problems that we see around us – global warming, wealth concentration, unemployment, poverty.”

Yunus is still committed to microfinance. He believes any problems are due to a lack of regulation that has allowed unscrupulous dealers to operate.

When done right, he said, the system could give poor people the freedom to improve their lives by building businesses instead of having to subsist on low-paying jobs.

“[With a job] you surrender yourself to somebody else’s wishes for the little money that they give you at the end of the month … that’s not what human beings are all about. Human beings are not built for serving somebody else. Human beings are very independent, packed with unlimited creative capacity,” he said.

“Our institutions have been designed the wrong way. If you have money, you get more money … but if you have no money, you don’t get any money. So you stay where you are.

“What microcredit has done is brought that finance at the lowest possible stage … finance is the oxygen of entrepreneurship. If you connect finance with people, people suddenly become very active, become alive, his mind starts ticking, he starts creating things. He’s looking at the world in a different way.”

Source:

Source: